|

|

March 22, 2024

Shweta Karki and Nihar R. Nayak

Abstract

Climate change poses significant challenges to sustainable development, particularly in vulnerable regions like Nepal. Despite this challenge, Nepal is resolutely working towards graduating from its LDC status by 2026 and attaining the SDGs by 2030. The Policy Brief investigates the intersection of climate change and sustainable development in Nepal, focusing on identifying the existing gap between climate change actions and sustainable development initiatives, and proposing strategies to bridge this gap effectively.

Although Nepal has established a plethora of policy frameworks, it grapples with effectively addressing climate-induced challenges. The alignment of political actors around common policy narratives does not always translate into a coherent framework for successful policy implementation, further underscoring the nuanced challenges Nepal encounters in bridging the gap between climate action and sustainable development.

Introduction

What geologists referred to as the leap from the Holocene to the Anthropocene, was a marked change of the influence that human activities had on earth’s climate,[1] particularly since the industrial revolution. Climate change as a global phenomenon carries wide connotations for differing sets of individuals, and has been conferred by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (1992) as “change of climate which is attributed directly or indirectly to human activity that alters the composition of the global atmosphere and which is in addition to natural climate variability observed over comparable time periods,”[2] simultaneously carrying wide repercussions. These repercussions result in disproportionate consequences,[3] and for developing nations that have done little to contribute to the growing threat, it means that they are faced with much to lose in the evolving crisis. This is also to note that while these states have occupied spaces within global negotiating platforms and when framing their scope of interests in reference to the global strategies, but the narratives and perceptions that guide the prospects for aligning, as well as defining, the climate discourse with sustainable development in practice are diverse. This policy brief aims to trace Nepal’s current course of climate action and its aspirations for sustainability and growth encapsulated within it. To do so, it becomes vital to grasp how the two ideas find conjunction in state practices today.

For a sizeable period, though climate-related stressors were mapped and assessed, its impacts on sustainable development (SD), along with the converse, were not systematically merged into discussions when devising policies.[4] Both concepts, emerging out of different traditions, or schools of thought, gained sharp traction during the 80’s and overlapped with regards to the “global dimensions of environmental problems,” generally looking at the issues of “inter-generational equity issues and on global environment, particularly climate change and biodiversity depletion,”[5] evident in the Brundtland Report and the Rio Summit in 1992, and have often provided varying ways to look at the issue.[6] Linking and defining these broad framed agendas within state mechanisms have been the challenge that many nations have faced on local and community levels. Concepts like risk reduction and resilience then pan out to mean something beyond just coping with certain shocks and “bouncing back,” incorporating notions of securing state and human capabilities as well as “a better adjustment to disasters” and mobilizing resources before a probable crisis.[7]

With the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) preceding it, there was a lack of clear focus on climate issues. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), introduced in 2015 through United Nations General Assembly resolution (70/1), provided a comprehensive framework that all member states unanimously adopted. This framework connected climate change with economic and human development agendas.[8] SDG 13 specifically targets building resilience and adaptive capacity to climate-induced disasters, adopting national policies, promoting renewable energy, and securing financial aid and investment for vulnerable countries.[9] In the same year, the Paris Agreement emerged as a landmark document where low and middle-income economies committed to reducing emissions and transitioning to clean energy, outlined through Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs).[10] However, coordination between these frameworks was limited until 2020.[11] The intertwining of sustainable development and climate action gained prominence as the impacts of climate-induced disasters were recognized as threats to national security. Global discussions within the climate debate increasingly focused on developing nations’ adaptation capacity, mitigation standards, loss and damage, and climate finance, influencing Nepal’s development narrative and resource constraints in addressing transboundary crises.

As a country seeking to graduate from the least developed country (LDC) status by 2026, and the SDGs nearing towards 2030, Nepal has been lagging in securing goals of sustainable development, especially its net-zero commitment by 2045.[12] The primary challenge is to move towards a low carbon growth and infrastructural development that goes hand in hand with protecting the ecosystems, and increasing resilience in the diverse sectors[13] that are sensitive to climate stressors. A recent study has mapped the graph of climate induced disasters that impact Nepal’s socio-economic conditions, and has noted that by 2050 the state is projected to incur annual GDP loses at 2.2%.[14] In a case scenario where climate-induced impacts are severe, just based on the impacts of floods on built infrastructure, the World Bank has cautioned that the estimated GDP could fall by 7%.[15] In a decade, the federal budget allocation had likewise for activities related to climate change, had gone from 10.34% in Fiscal Year (FY) 2014 to 33.98% in FY2023, though limited resources have been an impediment.[16] The Disaster Risk Reduction National Strategic Plan of Action (2018-2030) had provided basis for “at least 5 percent of the annual budget of every public institution” being allocated for disaster risk management (DRM).[17]

There’s growing awareness about environmental insecurities, leading governments and legal systems to address the crisis. This reflects the evolving standards of state inclusion of climate change as a threat, alongside existing gaps between political will, policies, and implementation. For instance, the Supreme Court’s 2018 ruling on a complaint highlighted Nepal’s Paris Agreement commitment, constitutional provisions (Article 51(g)), the unimplemented 2011 Climate Policy, and the need for climate justice and sustainable development.[18] The Court issued a writ of mandamus to enact a new climate law that would “(i) mitigate and adapt to the effects of climate change, (ii) reduce the consumption of fossil fuels and promote low carbon technologies, and (iii) develop scientific and legal instruments to compensate those harmed by pollution and environmental degradation, among other provisions.”[19] In 2019, the Environment Protection Act and the Forest Act was passed in response to it.[20] But alongside such changes, the problem of implementation and coordination has been an incessant matter since 1997 when the first the Environmental Protection Act was passed,[21] though with a new federal structure, the complexities have only given way to new challenges and opportunities.

In the peculiar case of climate action, while local levels and community actions are being noticed, intersections, and the narrow gaps in the integration, between science, policy and negotiations remain central to the understanding of Nepal’s challenges and opportunities when assessing the issue. There is a need of packaging the state’s threat perceptions, in consideration of its limitations, in context of climate risks within regional as well as global channels of negotiations. Within the domestic arena, a more concerted effort is required within and between the various sectors of governance, with the understanding that the ideas that link SD and climate action are complex, evolving in differing narratives within various dimensions of vulnerability.

Current Trends

Numerous studies have pointed out throughout the years that climate stressors and weather variations could impact poverty, and the poorest regions in the world would face the brunt of the climate crisis, facing food and water insecurity, alongside mass movements motivated by resulting shortages.[22] Nepal falls within such considerations, even with local, institutional and state efforts - though in some cases disjointed – piling into ascertaining the state’s overall graph of sensitivity to climate and disaster risks. For mountainous regions that are dependent on sectors of agriculture and tourism, climate-induced disasters that come in various forms including glacier lake outburst floods (GLOFs), impact their economy.[23] Even as newer concepts have emerged that have built into the concept of sustainable development in the state like the green, resilient, and inclusive development approach (or GRID), challenges come in the aspects of efficiently bridging such perceptions of sustainability with climate action, the kind of financial resource it would require and the state capacity to bridge local and community knowledge and experience of resilience when mapping these concepts out.

Understanding Nepal’s Vulnerability: Insecurities of a Small Developing State

Antonio Guterres stood at the foot of the Everest region in Nepal in 2023, and impressed upon the nature of the sensitive ecology of the mountains and how “the rooftops of the world are caving in,” highlighting the effects of a warming planet on the glaciers that carry potential to flood and devastate “low-lying countries and communities”.[24] Shortly after when addressing COP within the Climate World Action Summit, Nepal’s Prime Minister in his National Statement emphasized greatly on the aspects of climate justice, a concept that merges “the standards of human rights with issues of sustainable development and responsibility for climate change,”[25] and how the crisis has played out in the adaptation and mitigation efforts for Nepal that has faced “financial and technological gaps.”[26] It has been a long-standing concern for the country that in the face of a problem like climate change, the solutions only start with the formulation of national policy mechanisms, but then go on to necessitate a clear grid for implementation, that in turn needs a cohesive financial structure.

Nepal, a developing nation that has almost been in a transitory state for the past few decades, is located in the precarious Hindu Kush Himalayan (HKH) region, atop a tectonically active area, and as a mountainous country is particularly susceptible to the impacts of climate-induced disasters. During Nepal’s chairing of an event in COP28, attention was drawn to the absence of early warning systems (EWS), with resource availability not being a primary concern. However, it is worth noting that community-led EWS, despite facing some challenges, has been crucial for many communities in Nepal.[27]

Moreover, environmental insecurities also have an impacts on the existent socio-economic inequalities, for example in the case of marginalized communities and individuals, and are more pronounced,[28] and this has been a concern especially when looking at how without adequate socio-economic systems and structures of support, inequalities are likely to widen due to climate stressors.[29] When the question of vulnerability arises, there are several components that come into assessing the state’s degrees of responsiveness and resilience in dealing with the crisis.[30] Nepal has been incurring property losses amounting to more than USD 17.24 million on average due to climate induced events.[31] Adding to such numbers are the impacts on human development. 17.5% of Nepal’s population are living in multidimensional poverty, and 17.8% are vulnerable to it,[32] which means that the individuals are either already or at risk of experiencing deprivation across sectors of “monetary poverty, education, and basic infrastructural services,”[33] like health services. According to a report published by the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, climate change could “trigger a negative feedback loop between livelihoods and health,”[34] disproportionately impacting women from low-income groups, farmers, economically marginalized communities, and other groups that face added hindrances in accessing technical support.[35]

Nepal is a host to different climate zones and the impacts of variations in weather and climate are interspersed in wider observation. Changes in precipitation patterns as well as “increased flooding, heat stress on labor productivity and health, and heat stress on crops and livestock are expected to be a continual drag on growth.”[36] Further, the country also lies between Asia’s economic giants, India and China, which are included in the top ten global carbon emitters.[37] Adding to the observation, is also the matter that even if Nepal’s emissions are negligible, its emissions are growing, despite the Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) targets[38] and the state of air pollution in the country is inordinately high, exacerbating pre-existing sensitivities,[39] also taking into account that one of its largest import is still petroleum products.[40] So, the links drawn between climate change and sustainable development are interconnected and diverse – the nettings of which can be deciphered in studies that look both into how goals of sustainability in development activities are impacted by the warming planet, and also the ways in which policy behaviors towards sustainable development impact a state’s overall response to the climate issue.

Climate Action and Sustainable Development: Widening Goals and Lofty Ambitions

Following the signing of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change and the Kyoto Protocol, climate change became a significant concern reflected in Nepal’s 10th periodic plan (2002-2007).[41] This was followed by the 3-year interim plan (2007-2010), establishing the Carbon Trading Mechanism (CTM) for carbon trade, and the Climate Change Policy of 2011, where there were shifts from aspects of “disaster response and relief (1997–2002) to disaster risk reduction (2003–2008) and to climate change adaptation (2009–2011).”[42] This aligns with Nepal’s participation in The Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030, which succeeded the Hyogo Framework for Action. Nepal further reinforced its commitment by enacting the Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Act, 2074 (DRR&M, 2017), and the Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Rules, 2076 (2019).[43] The latter two documents provided a course of action for the government to enact programs and research on natural disasters and climate change (2017, Art. 11(c)), as well as ensure the formation of an expert committee to identify and provide suggestions DRR&M issues impacted by climate change (2019, Art. 4 (3e)).[44]

Additionally, when the Sustainable Development Status and Roadmap was also released by the National Planning Commission in 2017, a few years after the UNGA declaration was passed, it was with the understanding that the state was entering a new phase in its political and socio-economic changes as a young federal democracy. Climate was an issue that was framed within the document as an avenue for Nepal to assume an “international leadership role”[45] in and with “ambitious but realistic policy decisions,” regarding agriculture, clean energy and tourism were envisioned to “move Nepal towards a job-creating low-carbon economy.”[46] From then till the current 15th plan, climate has been a focused topic, where agendas and objectives have kept widening. Likewise, 2019 Climate Change Policy that replaced the 2011 policy, allowed for Constitutional provisions to be better brought into practice, addressing issues of inequality, climate finance, research and development, and adaptation in the agricultural sector.[47]

The basis for adaptation policies are seen through the National Adaptation Programme of Action in (NAPA, 2010) and the Local Adaptation Plans for Action (LAPA) framework, as well as the National Adaptation Plan Summary for Policy Makers in 2021.[48] Nepal’s long-term mitigation strategy has been “to achieve net zero GHG emissions by expanding hydropower for domestic and regional use, e-mobility, shifting away from fossil fuels for industrial processes, and reducing methane emissions from waste.”[49] Nepal has also submitted two NDCs, recently in 2020, as per its commitment to the Paris Climate Agreement. Referencing the 2019 policy, the sectoral areas were widened under the adaptation priorities and ambitious mitigation targets were written down.[50] In 2023, the National Adaptation Plan (2023) was introduced during the national climate summit that took place in Kathmandu that replaced NAPA and set priority adaptations and put forth a cost of USD 47.4 billion, with around USD 45.9 billion dependent on external support, and highest allocation given to adaptation in agriculture and food security.[51]

In 2021, with the endorsement of the Kathmandu Declaration that was signed by the Nepal Government, the Green, Resilient, Inclusive Development Approach (GRID) was brought within the fore of reframing sustainable development, outlining a proactive move towards building resilience to climate change and reducing risks to biodiversity loss, among other strategies, prioritizing inclusion, green investment and job creation, as well as resilient infrastructure.[52] The local governments were provided implementation responsibilities within the federal structure in Nepal’s government, and were placed in a vital position to translate the GRID approach into action.[53] A high-level event that was organized by the Ministry of Finance and Nepal 16 development partners in November, 2023 reiterated their commitments to finance and support the priority areas encompassed within the GRID approach.[54] Under GRID, Nepal and the World Bank have signed a USD 100 million concessional loan agreement,[55] as a part of its programmatic series to provide three concessional loans, the first of which has been paid out in September 2023,[56] alongside persistent remarks of it not being a part of climate finance. It remains to be seen how the development envisioned within the plan may impact aspects of adaptation in key socio-economic sectors and climate resilience.

However, these evolving dimensions of responsibilities in global discourses that come into narratives of vulnerabilities, alongside Nepal’s own commitments and policy mechanisms are merely starting points, and gaps are evident within the purview of resource availability as well as mobilization, political will and the policy implementation of the state.

Gaps between Climate Action and Sustainable Development:

The interplay among climate change, security, and development highlights Nepal’s challenges in addressing climate-induced stressors despite numerous policy frameworks. While political actors share common policy narratives, this does not ensure a coherent structure for successful implementation. Nepal’s political landscape, transitioning and federal structure, contribute to struggles regarding climate action, rights, and responsibilities across different tiers of governance. In reference to the above sections, below are brief points on those persistent gaps:

Experts have repeatedly criticized the Nepali government for its lack of disaster preparedness, often responding only after tragedies occur. This includes challenges in devising and implementing resilient policies, as seen during extreme weather events in 2021 and 2023, and the second COVID-19 wave. Issues such as ineffective communication of risks to vulnerable communities, gaps in local action plans, and the need for defined disaster management budgets have been highlighted.[57]

A research article, has also has put forth the argument that there is a “mismatch” between the authority granted to the local governments post-decentralization and the actual institutional capacity to develop policies and deliver results, underlining how “the development of climate knowledge and expertise remains concentrated in Kathmandu.”[58] The researchers outlined that even though some expertise have been gained on the federal scale and owing to climate initiatives that have received funding from external sources, national and local adaptation plans were mostly lacking “local-level baseline assessments.”[59] Pokharel, referencing the study noted that even though Constitutional provisions provide the local, federal and state levels with rights to respond to the climate impacts, there have been growing confusion persists with regards to coordination between the local and provincial governments, and the concerns surrounding capacity gaps as well as the issue of allocating financial budgets in coordination with the technical knowledge of experts.[60] The implementation structure mostly prioritizes the center and the communication gaps do not make it easier for local and federal governments to coordinate properly when lining development within climate action.

There have also been questions that have been leveled at the dichotomies persistent in political posturing and actual actions that have taken place on the ground. For example, as aforementioned the NDC have been a part of political speech and directives but the actual implementation has encountered critical reflections.[61]

There has been a general understanding that with the scale of climate risks in Nepal, climate finance requires greater attention and sharper focus in Nepal’s negotiating practices, considering that the NDC targets to reach realization would require almost USD 33 billion.[62] In the second NDC that Nepal submitted, it mentioned some ambitious climate finance projects, seen within its mitigation component that has set an unconditional target of generating 5,000 megawatts by 2030, that would level up to USD 3.4 billion, not including the cost of policy actions and measures.[63] For that, climate finance requires a cohesive place within Nepal’s policy projections of climate risks. In a workshop organized by the Ministry of Finance and the Asian Disaster Preparedness Center (ADPC), it was acknowledged that the aspect of climate finance itself needs to be clearly defined within Nepal’s initiatives and efforts.[64]

Risks, Insecurities and Challenges: Towering Waters and Flooding Fields

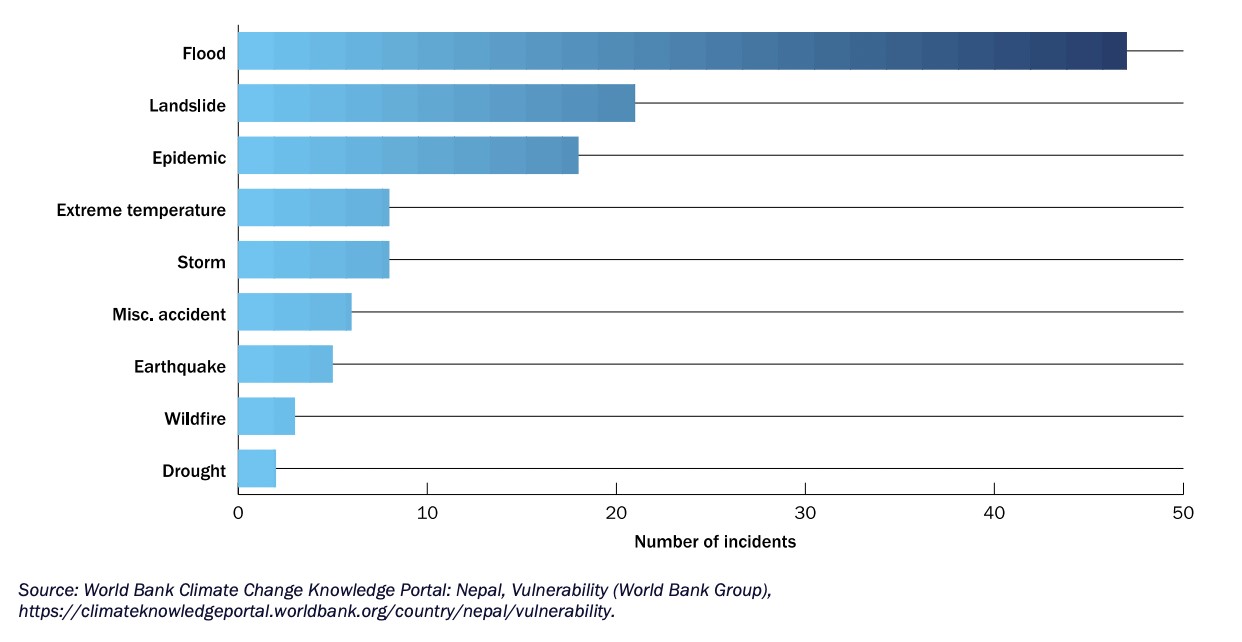

A study that mapped the impacts of climate-induced disaster on mortality reported that though climate disaster vulnerability was decreasing in Nepal, the impacts of disasters were increasing, where one of the reasons was considered to be the increased intensity and frequency of certain extreme weather events, possibly due to climate change.[65] An estimated number “5000 deadly climatic disasters were recorded in Nepal, which killed more than 10,000 people across the country,” in the previous three decades, particularly during the monsoon months.[66] The figure below illustrates the average annual occurrences of natural hazards from 1980-2020:[67]

Source: WBG, 2022.

The government has made efforts to ensure climate action contributes to a resilient and sustainable future for future generations. Sustainable development agendas have gained prominence, particularly in the past decade, as the risks and costs of the climate crisis are better understood. However, Nepal faces inherent challenges due to its physical geography and resource capabilities, which vary by risk and area. Climate variability across the country highlights differing risks, with the northern areas facing landslides and the southern regions facing heat, drought, and landslides. Mountainous regions are particularly vulnerable, requiring policies and actions tailored to their unique adaptation and mitigation needs.[68]

A recent study highlighting the highly risky cryosphere has mentioned that due to the rapid glacier retreat in the Himalayan region, by 2030 the number of individuals impacted by floods could increase twofold.[69] Water, food and energy security is a vital concern for the eight countries, including Nepal, in the area, especially if emissions are not curbed as per global commitments by the states and the glacial ice continues to melt. The HKH has been called a host to the “water towers” because it supplies freshwater through major transboundary rivers across the region. This has been a long-standing concern for the states in the region that a warming planet could first lead to an increase in the water levels with a drastic decrease later on, impacting water availability for communities that are dependent on freshwater for sustaining their fields and livelihoods. The concern also extends to the hydropower sector as well as the infrastructural damage that any major event could cause, raising the risk factor for investment within these key sectors of development.

To focus on key analysis starting points, let’s examine the underlying threat perceptions and interests:

There are other emerging trends and narratives to consider as well. In-Migration and cross-border, for example, has been linked with climate-induced disasters and even existing conflict patterns in some cases. Climate-induced migration is a term that has recently been brought into global dialogue platforms, whereby in certain “hotspots” living conditions start to negatively impact livelihoods and migration becomes a strategy of adaptation as well as a forced outcome in some scenarios.[81] Nepal could be impacted by either displacement or scarcity issues, and marginalized communities are further limited in their abilities to choose migration as an option.[82]

Amplifying Insecurities: Concerning Vulnerable Groups in Nepal

Vulnerable and marginalized groups face heightened climate risks, highlighting the issue of climate justice. Their limited participation in decision-making exacerbates these challenges. Efforts have been made to integrate traditionally vulnerable groups into climate discussions, such as including women in Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) practices.[83] But to sum up the basic ideas, vulnerable groups face limitations on their fundamental capabilities to not just access technical and financial assistance but also require greater focus when devising specific policy strategies and action plans. For example, individuals who come from low-income groups and lesser years of schooling are impacted on a greater scale, experiencing more fatalities.[84] To add to it and highlight a few cases, are the following considerations:

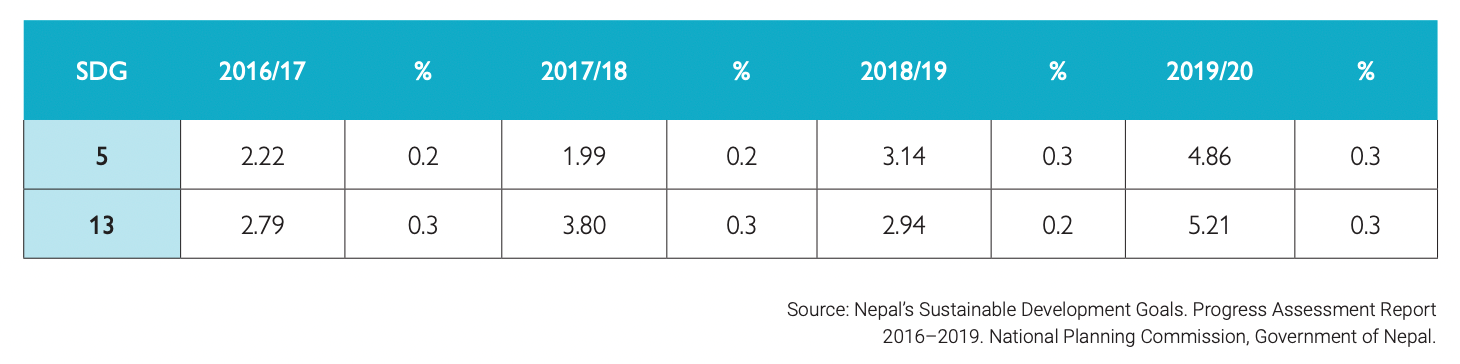

The gender-climate nexus has been much discussed in the context of Nepal’s pre-existing social and economic inequalities. Policies like have attempted to integrate the gender equality and social inclusion (GESI)[85] when factoring in development concepts and budget allocation as the table below shows the budget allocation for climate action and gender equality, in NPR billion,[86]

Source: ICIMOD, UNEP, and UN Women, 2021.

The same study, however also stated that an intersectional approach was necessary across the various tiers of institutional engagements, and that without a concerted effort to do so, policies and interventional strategies would not fully pan out. With regards to persistent “situational vulnerabilities,” pertaining to certain social groupings like caste and class, women who come from marginalized groups, live away from the center and in disaster-prone regions are the least likely to receive benefits from “development and climate change related resources and opportunities.”[87]

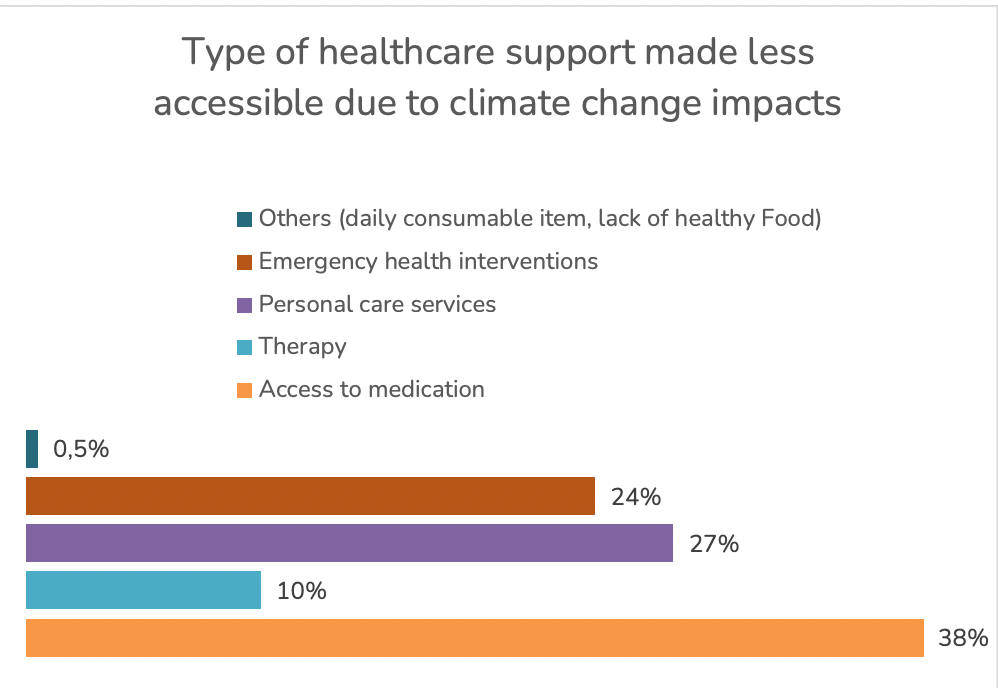

Persons with Disabilities (PwDs) are also considered to be inordinately vulnerable to climate impacts. Though the study lacks sufficient data, there are understandings that line with the assumptions that in cases of climate hazards and extreme weather events persons with disabilities find it significantly more difficult to access health services and have been provided with little familiarity to early warning systems, with almost 85% unaware of such mechanisms.[88] In the case of impacts of climate change on humanitarian services and healthcare services, within the wider context of access, the figure shows the challenges that PwDs face:

Source: Jennifer M'Vouama, Mosharraf Hossain, Sukharanjan Sutter, and Mahesh Ghimire, 2023.[89]

It is necessary to grasp that climate change acts as a catalyst – it is a threat multiplier that exacerbates already existing inequalities and conflict paradigms. Another study noted the “intersecting impacts” where “Disability discrimination is amplified by multiple and intersecting exclusion due to Indigeneity, poverty, language, and insufficient education and legal awareness,” arguing for a inclusivity responses when dealing with structural inequalities, gaining on the idea of “disability climate justice.” [90] This was based on a study done by Social Science Baha, whereby “intersectional” vulnerabilities were highlighted based on existent trends of structural inequality, as it was observed that PwDs faced limitations or were excluded when accessing resources and opportunities when coming from marginalized communities (based on caste and ethnicity) within the state in post-disaster scenarios.[91] These cases are examples of the intersectional inequalities where climate stressors disproportionately heighten the scope of insecurities for disadvantaged groups within the socio-economic structure. The approach towards development requires a coordinated understanding that addresses and further highlights these elements of vulnerabilities.

Conclusion and Recommendations

According to the data from the Voluntary National Review 2020, Nepal has made commendable progress in achieving SDG1 to SDG9. There has been notable societal implementation of SDG programs since 2016. However, despite these positive developments, certain sectors still lag behind. The following recommendations could be instrumental in achieving the remaining goals by 2030.

[1] Kate Meyer and Peter Newman, Planetary Accounting: Quantifying How to Live Within Planetary Limits at Different Scales of Human Activity, (Singapore: Springer Nature, 2020), 12; S. Bastianoni, F. M. Pulselli, L. Coscieme and N. Marchettini, “Instructions for a Sustainable Anthropocene,” Anthropocene Science 1 (2022): 404-409.

[2] “United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change,” United Nations, 1992, https://unfccc.int/files/essential_background/background_publications_htmlpdf/application/pdf/conveng.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2024).

[3] “Social Dimensions of Climate Change,” The World Bank, 01 April 2023, https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/social-dimensions-of-climate-change (accessed on 20 March 2024).

[4] Stewart Cohen, et al., “Climate change and sustainable development: towards dialogue,” Global Environmental Change 8, no. 4 (1998): 341-343.

[5] Natasha Girst, “Positioning Climate Change in Sustainable Development Discourse,” Journal of International Development 20 (2008): 786.

[6] Stewart Cohen, et al., 343.

[7] Vivek Thomas, Praise for Risk and Resilience in the Era of Climate Change (Singapore: Springer

Nature Singapore Pte Ltd, 2023): 3-4.

[8] “The 17 Goals,” United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 25 February 2024).

[9] “Climate Action,” The Global Goals, https://www.globalgoals.org/goals/13-climate-action/ (accessed on 25 February 2024).

[10] “The Science is Clear: Sustainable Development and Climate Action are Inseparable,” Nature, August 29, 2023, https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-023-02686-3 (accessed on 25 February 2024).

[11] “Blog: Climate action and sustainable development – Aligning the Paris Agreement and Agenda 2030,” The Commonwealth, October 2, 2023, https://thecommonwealth.org/news/blog-climate-action-and-sustainable-development-aligning-paris-agreement-and-agenda- 2030#:~:text=Both%20serve%20as%20comprehensive%20policy,until%20as%20recent%20as%202020 (accessed on 25 February 2024).

[12] “Least Developed Countries Are Seriously Off-Track In Achieving Sustainable Development Goals, Says PM Dahal,” The Kathmandu Post, 19 September 2023, https://kathmandupost.com/national/2023/09/19/least-developed-countries-are-seriously-off-track-in-achieving-sustainable-development-goals-says-pm-dahal (accessed on 25 February 2024).

[13] Das, et al., “Long term strategies: low carbon growth, resilience and prosperity for Least Developed Countries,” Climate Analytics, 20 July 2022, https://climateanalytics.org/publications/long-term-strategies-low-carbon-growth-resilience-and-prosperity-for-least-developed-countries (accessed on 25 February 2024).

[14] Christelle Cazabat et al., Disaster Displacement: Nepal Country Briefing (n.p. IDMC and Asian Development Bank, 2022), 11, https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/845106/disaster-displacement-nepal-country-briefing.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2024).

[15] The World Bank Group, Nepal Country Climate and Development Report (Washington: The World Bank Group, 2022), 26, https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/30a1cb25-232c-41ab-bd96-7046d446c2fc/content (accessed on 25 February 2024).

[16] The World Bank Group, Nepal Country Climate and Development Report, 19-20.

[17] ibid, 20.

[18] “Shrestha v. Office of the Prime Minister et al.,” Sabin Centre for Climate Change Law, last modified 2024, https://climatecasechart.com/non-us-case/shrestha-v-office-of-the-prime-minister-et-al/#:~:text=In%20a%20decision%20issued%20on,the%202015%20constitution%20required%20action (accessed on 25 February 2024).

[19] ibid.

[20] ibid.

[21] ibid.

[22] Ruma Bhargava and Megha Bhargava, “The climate crisis disproportionately hits the poor. How can we protect them?” World Economic Forum, 13 January 2023, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2023/01/climate-crisis-poor-davos2023/; “Rapid, Climate-Informed Development Needed to Keep Climate Change from Pushing More than 100 Million People into Poverty by 2030,” The World Bank, 08 November 2015, https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2015/11/08/rapid-climate-informed-development-needed-to-keep-climate-change-from-pushing-more-than-100-million-people-into-poverty-by-2030 (accessed on 25 February 2024).

[23] Madsen, M. , Climate Change in Polar and Mountainous Regions,

International Atomic Energy Agency, 18 August 2014, https://www.iaea.org/newscenter/news/climate-change-polar-and-mountainous-regions (accessed on 25 February 2024).

[24] “‘Stop the madness’ of climate change, UN chief declares,” UN News, 30 October 2023, https://news.un.org/en/story/2023/10/1142987 (accessed on 25 February 2024).

[25] Mary Robinson, Climate Justice: Hope, Resilience, and the Fight for a Sustainable Future (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2018), 19.

[26] “Statement by Prime Minister Pushpa Kamal Dahal at the COP28, Dubai, UAE, 02 December 2023,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Government of Nepal, 02 December 2023, https://mofa.gov.np/statement-by-prime-minister-and-leader-of-nepali-delegation-right-honourable-mr-pushpa-kamal-dahal-prachanda-at-the-28th-conference-of-parties-on-climate-change-cop28-dubai-uae-02-december-202/ (accessed on 25 February 2024).

[27] Diwakar Pyakurel, “How a low-cost early warning system across the Nepal-India border saves lives every monsoon,” Online Khabar, 12 March 2023, https://english.onlinekhabar.com/early-warning-system-nepal-india.html (accessed on 25 February 2024).

[28] “Risks: Historical Hazards,” Climate Change Knowledge Portal, World Bank, https://climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org/country/nepal/vulnerability (accessed on 21 February 2024); Jaya Ram Karki, Prabhat Kumar and Binod Baniya, “Climate Change and Mountain Environment in Context of Sustainable Development Goals in Nepal,” Applied Ecology and Environmental Sciences 10, no. 9 (2022): 589.

[29] “Climate Risk Country Profile,” World Bank Group, Asian Development Bank, 2021, https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/677231/climate-risk-country-profile-nepal.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2024).

[30] Shardul Agrawala, et al, “Development and Climate Change in Nepal: Focus on Water Resources and Hydropower, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2003, https://www.oecd.org/countries/nepal/19742202.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2024).

[31] Samjwal Ratna Bajracharya et al., Inventory of glacial lakes and identification of potentially dangerous glacial lakes in the Koshi, Gandaki, and Karnali River Basins of Nepal, the Tibet Autonomous Region of China, and India.

[32] “Briefing note for countries on the 2023 Multidimensional Poverty Index,” Human Development Reports, UNDP, 2023, https://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/Country-Profiles/MPI/NPL.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2024).

[33] “Multidimensional Poverty Measure,” The World Bank, last modified December 19, 2023, https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/poverty/brief/multidimensional-poverty-measure#:~:text=What%20is%20the%20Multidimensional%20Poverty,more%20complete%20picture%20of%20poverty (accessed on 25 February 2024).

[34] Aditi Kapoor et al., “Climate Change Impacts on Health and Livelihoods: Nepal Assessment,” International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, April 2021, https://reliefweb.int/report/nepal/climate-change-impacts-health-and-livelihoods-nepal-assessment (accessed on 21 February 2024).

[35] Aditi Kapoor et al., “Climate Change Impacts on Health and Livelihoods: Nepal Assessment,” 10-11.

[36] “Key Highlights: Country Climate and Development Report for Nepal,” International Finance Corporation, World Bank Group, 14 September 2022, https://www.ifc.org/en/insights-reports/2022/nepal-country-climate-and-development-report (accessed on 25 February 2024).

[37] “Who Releases the Most Greenhouse Gases,” World 101, Council of Foreign Relations, July 25, 2023, https://world101.cfr.org/global-era-issues/climate-change/who-releases-most-greenhouse-gases (accessed on 25 February 2024).

[38] “Integrating Climate Change into Nepal’s Development Strategy Key to Build Resilience, Says New World Bank Group Report,” The World Bank, 15 September 2022, https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2022/09/15/integrating-climate-change-into-nepal-s-development-strategy-key-to-build-resilience-says-new-world-bank-group-report#:~:text=As%20Nepal's%20economy%20grows%2C%20it,emission%20rate%20is%20growing%20rapidly (accessed on 21 February 2024).

[39] Shuvam Rijal, “Air Pollution: One of Nepal’s Key Policy Failures,” 01 April 2022, https://www.recordnepal.com/air-pollution-one-of-nepals-key-policy-failures. Arjun Poudel, “Air quality reaches ‘unhealthy’ levels in Kathmandu Valley, sparking public health concerns,” The Kathmandu Post, 07 November 2023, https://kathmandupost.com/climate-environment/2023/11/07/air-quality-reaches-unhealthy-levels-in-kathmandu-valley-sparking-public-health-concerns (accessed on 25 February 2024).

[40] Krishana Prasain, “Nepal undermining hydropower as it seeks to ease fuel imports, experts say,” The Kathmandu Post, 30 April 2023, https://kathmandupost.com/money/2023/04/30/nepal-undermining-hydropower-as-it-seeks-to-ease-fuel-imports-experts-say (accessed on 21 February 2024).

[41] Luni Piya, et al., “Climate Change in Nepal: Policy and Programs,” in Socio-Economic Issues of Climate Change (Springer: Singapore, 2019), 35.

[42] Piya, Maharjan and Joshi, 36.

[43] “Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Act, 2074 and Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Rules, 2076 (2019),” Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of Nepal, 2019, https://www.dpnet.org.np/public/uploads/files/DRRM_Act_and_Regulation_english%202022-04-13%2007-11-33.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2024).

[44] ibid.

[45] National Planning Commission, Government of Nepal, “Sustainable Development Goals Status and Roadmap: 2016 – 2030,” United Nations Development Programme, 21 February 2018, https://www.undp.org/nepal/publications/sustainable-development-goals-status-and-roadmap-2016-2030 (accessed on 25 February 2024).

[46] National Planning Commission, Government of Nepal, “Sustainable Development Goals Status and Roadmap: 2016 – 2030,” 4.

[47] “National Climate Change Policy,” Climate Change Laws of the World, 2020, https://climate-laws.org/document/national-cimate-change-policy_db96 (accessed on 25 February 2024).

[48] Center for Excellence in Disaster Management & Humanitarian Assistance, Nepal: Disaster Management Reference Handbook (n.p. Center for Excellence in Disaster Management & Humanitarian Assistance, September 2023), 32, https://reliefweb.int/report/nepal/disaster-management-reference-handbook-nepal-september-2023 (accessed on 25 February 2024).

[49] ibid.

[50] “Second Nationally Determined Contributions,” Ministry of Health and Population, Government of Nepal, December 8, 2020, https://climate.mohp.gov.np/attachments/article/167/Second%20Nationally%20Determined%20Contribution%20(NDC)%20-%202020.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2024).

[51] “National Adaptation Plan (NAP) 2021-2050: Summary for Policymakers,” Government of Nepal, 2023, https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/NAP_Nepal.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2024).

[52] Sneha Shrestha, “Nepal’s Green, Resilient, and Inclusive Development (GRID),” Nepal Economic Forum (NEF), 27 September 2021, https://nepaleconomicforum.org/nepals-green-resilient-and-inclusive-development-grid/ (accessed on 25 February 2024).

[53] “Integrating climate change into Nepal’s development strategy key to build resilience,” The World Bank, 15 September 15 2022, https://www.preventionweb.net/news/integrating-climate-change-nepals-development-strategy-key-build-resilience-says-new-world (accessed on 25 February 2024).

[54] “Nepal: Government, Development Partners Prioritize Investment in Green, Resilient, and Inclusive Development,” The World Bank, 02 November 2023, https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2023/11/02/nepal-government-development-partners-prioritize-investment-in-green-resilient-and-inclusive-development?cid=sar_fb_nepal_xx_ext (accessed on 21 February 2024).

[55] “Nepal and World Bank Sign $100 Million Concessional Loan Agreement to Support Nepal’s Green, Resilient, and Inclusive Development,” Ministry of Finance, Government of Nepal, https://www.mof.gov.np/uploads/document/file/1661772531_PR_Signing%20GRID%20DPC_Eng.pdf (accessed on 02 March 2024).

[56] “Green, Resilient, and Inclusive Development (GRID) in Nepal,” The World Bank, https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/nepal/brief/green-resilient-and-inclusive-development-in-nepal#:~:text=%22The%20GRID%20approach%20departs%20from,a%20cascading%20series%20of%20crises (accessed on 20 March 2024).

[57] Chandan Kumar Mandal, “Flood devastation in Melamchi not only because of rains,” The Kathmandu Post, 17 June 2021, https://kathmandupost.com/climate-environment/2021/06/17/flood-devastation-in-melamchi-not-only-because-of-rains (accessed on 02 March 2024).

[58] Dil B. Khatri, et al., Multi-scale politics in climate change: the mismatch of authority and capability in federalizing Nepal, Climate Policy 8 (2022): 1090. 1084-1096, https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2022.2090891 (accessed 02 March 2024).

[59] ibid, 1087.

[60] Kushal Pokharel, “Analysis: How decentralisation in Nepal is undermining climate action,” PreventionWeb, 28 August 2022, https://www.preventionweb.net/news/analysis-how-decentralisation-nepal-undermining-climate-action (assessed on 02 March 2024).

[61] Subash Pandey, “Catalysing Nepal’s Commitment,” The Kathmandu Post, 07 September 2023, https://kathmandupost.com/columns/2023/09/07/catalysing-nepal-s-climate-commitment (assessed on 02 March 2024).

[62] Sajira Shrestha, “Experts highlight need for intensifying diplomatic endeavors as Nepal's climate finance landscape remains poor,” My Republica, 02 September 2023, https://myrepublica.nagariknetwork.com/news/experts-highlight-need-for-intensifying-diplomatic-endeavors-as-nepal-s-climate-finance-landscape-remains-poor/#/google_vignette (assessed on 02 March 2024).

[63] Second Nationally Determined Contributions,” Ministry of Health and Population, Government of Nepal.

[64] Rojee Joshi, et al., Accessing Climate Finance in Nepal: Issues and Options (Bangkok: Asian Disaster Preparedness Center: 2023), 4, https://www.adpc.net/Igo/category/ID1861/doc/2023-uAQc62-ADPC-Accessing_Climate_Finance_in_Nepal_ForWeb.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2024).

[65] Dipesh Chapagain, et al., “Declining vulnerability but rising impacts: the trends of climatic disasters in Nepal,” Regional Environmental Change 22, no. 55 (2016): 9.

[66] ibid, 5.

[67] The World Bank Group, Nepal Country Climate and Development Report, 12.

[68] Mattia Amadio et al., Climate risks, exposure, vulnerability and resilience in Nepal (Washington DC: World Bank, 2023), https://reliefweb.int/report/nepal/climate-risks-exposure-vulnerability-and-resilience-nepal#:~:text=While%20landslides%20are%20more%20likely,%2C%20heat%2C%20and%20drought%20hazards (accessed on 20 March 2024).

[69] “Disaster Displacement: Nepal country briefing, ADB, 2022, https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/845106/disaster-displacement-nepal-country-briefing.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2024).

[70] Mattia Amadio et al., 2.

[71] Monica Upadhyay, “Banking on apples: How women in rural Nepal are tackling climate challenges,” World Food Programme, 13 October 2023, https://www.wfp.org/stories/banking-apples-how-women-rural-nepal-are-tackling-climate-challenges (accessed on 20 March 2024).

[72] “Nepali farmers diversify their income streams amidst climate crisis,” UNEP, 27 September 2022, https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/nepali-farmers-diversify-their-income-streams-amidst-climate-crisis (accessed on 20 March 2024).

[73] Nilhari Neupane, et al., Enhancing the resilience of food production systems for food and nutritional security under climate change in Nepal, Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 6 (2022): 1-11.

[74] Dinanath Bhandari, “Food Security amidst Climate Change in Nepal” Mountain Forum Bulletin VIII, no. 1 (2008): 21-24.

[75] Santosh Nepal et al., “Achieving water security in Nepal through unravelling the water-energy-agriculture nexus, International Journal of Water Resources,” International Journal of Water Resources Development 37, no. 1 (2021): 8-10.

[76] Arjun Poudel, “Climate change adds risk to investments in hydropower,” The Kathmandu Post, 05 July 2023, https://kathmandupost.com/climate-environment/2023/07/05/climate-change-adds-risk-to-investments-in-hydropower#:~:text=Our%20infrastructures%20should%20be%20made,first%20spell%20of%20the%20monsoon (accessed on 20 March 2024).

[77] Chandan Kumar Mandal, “Flood devastation in Melamchi not only because of rains,” The Kathmandu Post, 17 June 2021, https://kathmandupost.com/climate-environment/2021/06/17/flood-devastation-in-melamchi-not-only-because-of-rains#:~:text=Experts%2C%20however%2C%20say%20rainfall%20is,such%20a%20level%20of%20disaster (accessed on 20 March 2024).

[78] Diwakar Pyakurel, “How a low-cost early warning system across the Nepal-India border saves lives every monsoon,” Online Khabar, 12 March 2023, https://english.onlinekhabar.com/early-warning-system-nepal-india.html (accessed on 20 March 2024).

[79] Subash Pandey, “Climate Finance Dilemma,” The Kathmandu Post, 01 March 2023, https://kathmandupost.com/columns/2023/03/01/climate-finance-dilemma#:~:text=Nepal%20anticipates%20climate%20finance%20of,and%20%2446.4%20billion%20by%202050 (accessed on 20 March 2024).

[80] Diwakar Pyakurel, “Nepal’s ‘climate loan’ triggers dispute over fairness and definitions,” The Third Pole, 08 November 2022, https://www.thethirdpole.net/en/climate/nepal-climate-loan-triggers-dispute-over-fairness-and-definitions/ (accessed on 20 March 2024).

[81] Jana Junghardt and Regis Blanc, “How Climate Change Influences Migration Patterns,” Helvetas, 19 June 2023, https://www.helvetas.org/en/switzerland/how-you-can-help/follow-us/blog/migration/How-Climate-Change-Influences-Migration%20Patterns#:~:text=In%20some%20areas%20of%20the,climate%20change%20and%20resulting%20extremes (accessed on 20 March 2024).

[82] Shuvam Rijal, “Nepal’s climate change migrants,” The Record, 01 February 2022, https://www.recordnepal.com/nepals-climate-change-migrants (accessed on 20 March 2024).

[83] Sajana Shrestha, “Role of women in disaster risk reduction (DRR) and climate change in Nepal,” Prevention Web, 08 March 2022, https://www.preventionweb.net/news/role-women-disaster-risk-reduction-drr-and-climate-change-nepal (accessed on 20 March 2024).

[84] The World Bank Group and the Asian Development Bank, Climate Risk Country Profile: Nepal (Washington: WBG and ADB, 2021): 19-20.

[85] Chanda Gurung Goodrich, Dibya Devi Gurung, and Aditya Bastola, The State of Gender Equality and Climate Change in Nepal (Kathmandu: ICIMOD, UNEP, UN Women, 2021).

[86] ibid, 24.

[87] ibid, 36.

[88] Jennifer M’Vouama, et al., Persons with disabilities and climate change in Nepal: Humanitarian impacts and pathways for inclusive climate action (n.p. A Humanity & Inclusion publication, Protection and Risk Reduction Technical Division, Disaster Risk Reduction and Climate Change Adaptation Unit, 2023), 7.

[89] M’Vouama et al., 32.

[90] Pratima Gurung, Penelope J.S. Stein, and Michael Ashley Stein, “Intersectionality, Indigeneity, and Disability Climate Justice in Nepal,” The Petrie-Flom Center staff, Harvard Law, 29 February 2024, https://blog.petrieflom.law.harvard.edu/2024/02/29/intersectionality-indigeneity-and-disability-climate-justice-in-nepal/ (accessed on 20 March 2024).

[91] Austin Lord et al., “A Study of the Challenges Faced by Persons with Disabilities in Post-Earthquake Nepal,” United Nations Development Programme, May 2016, https://www.un.org/disabilities/documents/2016/Disaster-Disability-and-Difference_May2016_For-Accessible-PDF.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2024).